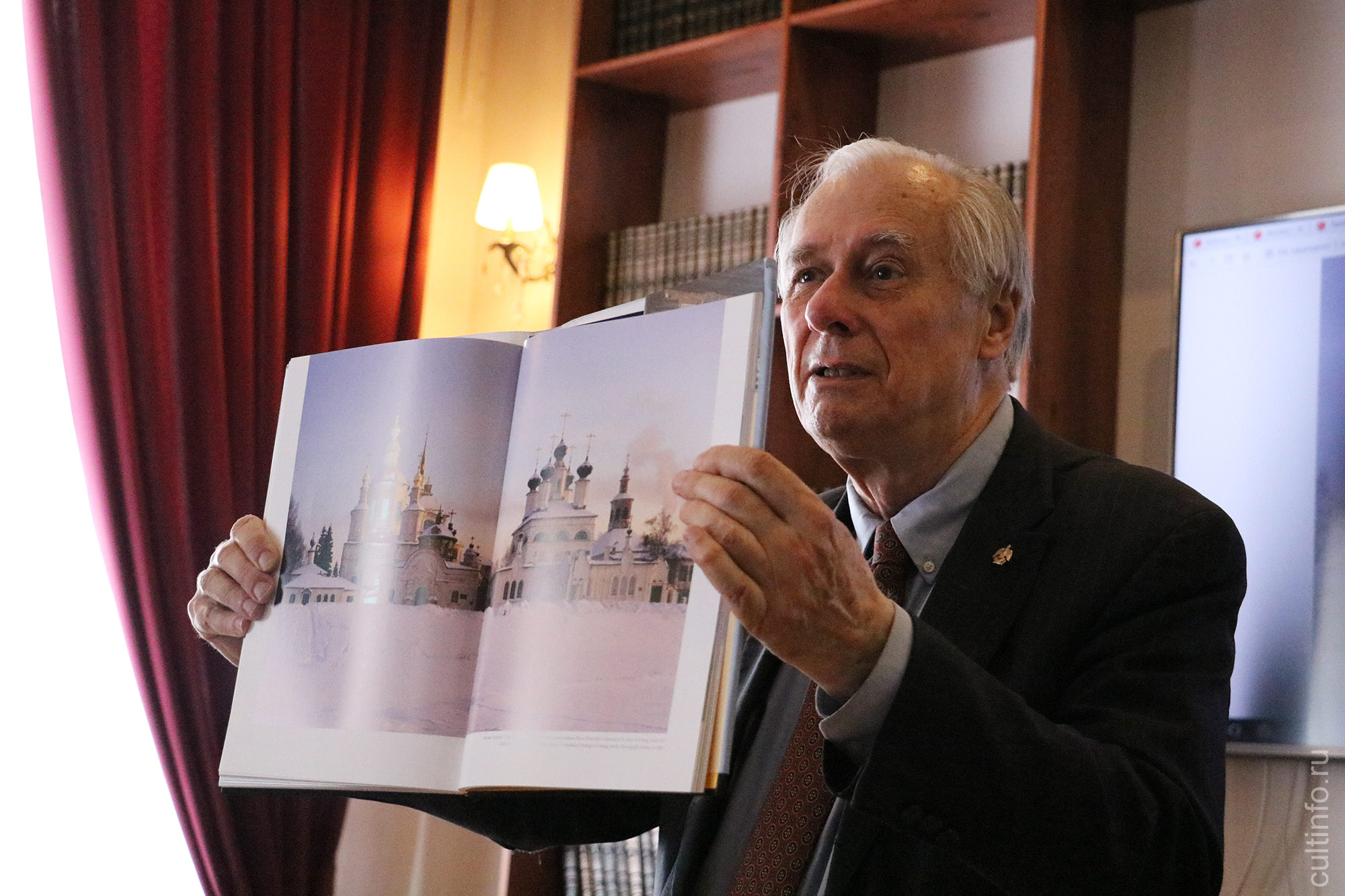

William Brumfield—a historian, photographer and professor of Slavic studies at Tulane University in New Orleans—has for many years been occupied with the study and popularization of Russian architectural monuments, with particular emphasis on the Russian Norh and the Vologda territory. During the past week he met on two occasions with Vologda residents. The first event was a lecture for students at Vologda State University, who liked he American Slavist for his engaged interest. The following event was a meeting with the general public in the recently renovated Rare Books Hall of the Vologda Regional Library. Those who were interested in the scholar’s activity but could not attend the meeting can learn about it through this report on cultinfo.ru.

“Vologda occupies a very big place in my work,” Brumfield repeatedly noted at the meeting with Vologda residents. He included Vologda’s St. Sophia Cathedral in his fundamental book A History of Russian Architecture, which appeared in 1993, even though he had not yet been to Vologda—an exception to the researcher’s position of not writing about monuments that he had not personally seen. His visual acquaintance with the Vologda St. Sophia occurred on his first visit to Vologda, in 1995.

With warmth and nostalgia, Brumfield reminisced about his first visits to Vologda: “Our small group of American scholars stayed in the so-called “Obkom hotel,” my favorite place in the 1990s. Althtough, of course, the main thing was not the creature comforts, but our acquaintances, our meetings and our work. So many trips to the Vologda region! The photographs then appeared in my books (available in the library) and on the site devoted to the culture of the Vologda region—cultinfo.ru.

Opening the section of the site devoted to his work, Brumfield wryly noted that the portrait photograph was “not exactly recent ... Let’s say last year’s.” By the way, this is the same photograph that appears on Brumfield’s identification document as a member of the Russian Academy of the Fine Arts, with the signature of Tsurab Tsereteli. Seeing his book Vologda Album in the hands of one library reader, Brumfield remembered that during a visit in 2005 Tsereteli had received this book from the chief of the region. “And a year later I was elected a member of the Russian Academy of the Fine Arts.” Showing the document with the testamentary signature, Brumfield added: “this is like a second passport. The signature of Tsurab Tsereteli can be a great help.”

At the meeting Brumfield was of course asked where this American citizen gained such an involvement in Slavic studies and Russian culture. “I grew up in the American South in a very complicated time. You have probably read Gone with the Wind, which is set in the same places where my childhood occurred. This was not a typical American narrative; there was much that was tragic. From my youth these questions—where is justice, who is at fault—occupied me. And when I began to read the novels of Tolstoy, they acted on me as a healing spirit. I suddenly understood that I was not alone. There are other people who also pose these accursed questions to themselves. It all began from that.”

“My moher loved Russian music. I remember those old records, Tchaikovsky, The Nutcracker Suite .... The music of genius! But, perhaps, my father’s wisdom played the decisive role. My father was born in 1895. He was 49 when I was born. He served in the US Marine Corps on the western front during the First World War. He lived through all that meatgrinder, and in France in 1918 he saw interned Russians. They were part of a large Russian contingent, an expeditionary corps of more than 100,000 men who had served in the French army at the request of the president of France. They fought and died, and after the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, the French became afraid and interned them. When I was around eight years old, during the Korean War, I was playing at soldiers and killing “Russian Communists” when my father interrupted me and said: ‘Son, the Russians are not our enemies. I saw them then, after the First World War. They were our allies, and they were kept like cattle. I felt pity for them....’ For me this was like a clap of thunder on a clear day. From that moment I began to look at these things differently.”

Brumfield first visited the USSR in 1970 as a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley. To this day the scholar has lived in the USSR and Russia for a total of almost fifeen years, traveling throughout the Russian North and phototgraphing examples of traditional architecture. In particular Brumfield has directed a special intensive attention to Vologda’s wooden architecture, as well as to the churches of Vologda and the Vologda region. Brumfield himself calls his interest in Russian architecture and, first and foremost, in religious architecture “God’s plan”. “I am a scholar of literature, a Slavist, and sometimes colleagues say to me ‘Why are you doing this photography? But through photography Russia opened my eyes. In a literal sense. God’s plan, there are no other words for it.” The scholar also remembers his thoughts and feelings from memorials to Soviet soldiers who died on the fronts of the Great Patriotic War. “At first I did not think about this. But in every village and in every town I have photographed monuments and memorials to those who perished in that war—when Russia, the Soviet Union saved the world. But you know at what cost—hundreds, thousands of dead from every town, from every village. Sometimes these villages no longer exist, but the momument is there, nonetheless. And how the Russian people bore up .... I talk about this with my students, because in the West they don’t know about this. And sometimes, I feel that they do not want to know. But your country held together. For me that is a mystery. That is probably the soul of the people.”

Brumfield always emphasizes that he does not get involved in politics, although at every meeting he is asked about the complicated relations between the US and Russia. “This is not my business, I am a scholar. And I have been involved in this study for so long, a value so much your culture. There are American colleagues with a narrow perspective, let’s say. As it is said in the Bible, they have eyes, but they see not. But quite simply you have to see. And my work is a bridge for this vision.” And he emphasizes that in America by no means everyone shares the official position of the powers that be: Brumfield’s last book about the architecture of he Russian North (in English) appeared thanks to financial support from American sponsors, and by the end of 2019 it is supposed to appear in Russian. “In April I had a personal meeting with the ambassador of Russia to the US, Anatoly Antonov. He said humorously: ‘Professor, you speak Russian better than we do.’ Yes, he is a diplomat, but his words were really not far from the truth. He and I had a very good, warm talk. It is good that such meetings occur despite everythting, and that there are people who maintain these connections, these contacts on a human and cultural level.”

Brumfield’s archive contains more than 140,009 photographs. “Photographs are a time machine,” says the researcher. “With their help we are transported to another time, to another epoch. In this way we preserve memory about heritage.” A confirmation of this is the fact that photographs taken by Brumfield show more than a few churches that no longer exist—destroyed, demolished by fires. Brumfield’s photographs are always precisely dated and thus form a distinctive chronicle. “Thank God that I was able to photograph certain wooden churches before their destruction; one can see what ,.they were,” he said while showing, for example, photographs made in 2000 for the irrevocably lost Dormition Church in Kondopoga—a unique monument burned to the ground in the summer of 2018. And since the very ttheme that Brumfield is engaged in—the preservation of historic and cultural heritage, of architectural monuments—is extremely acute and difficult, the questions that arose at the meeting with Vologda residents were aften about painful matters. Thus, for example, in response to a question about the necessity, in his opinion, of recreating lost churches, Brumfield answered directly: “Is it worth it? Is it worth it when there are other churches which are barely standing? One needs to think about them, if means are limited. I thinik so. But others think otherwise. I don’t judge, there are various approaches. In he final analysis I am simply a photographer, a scholar, an observer. I do this not only for the sake of art, but also for the sake of scholarship. And my resource on cultinfo.ru is a genuine documentary site. Sometimes I am criticized that there are to many duplicate views.... But I especially insist that all the photographs be included, because this is a genuine archival resource, made on a scholarly basis.”

In his trips Brumfield has also tried to record that which surrounds a monument. With tenderness he showed a photograph of a horse taken in one of the Vologda villages. “I love the little northern horses! They are so patient and reliable.” He also expressed his admiration for Russian off-road vehicles, thanks to which he was able to reach sites even in extreme conditions. “The Volga was a good car. But for such places, the Uazik is better. I remember how in the Velsk district we got stuck in a large puddle. The driver got out and he—how do you say in Russian?—in order to make the front axle work, he had to engage it. But not from inside the vehicle—that is too simple. He did this in some incredible way. And we sped off,

Mikhail Karachev, the president of the Vologda branch of the Writers’ Union of Russia, remembered how he traveled with Brumfield to Totma and Velikii Ustiug in 40-degree frost. “I will never forget his shoes with thin leather soles, and how he climbed over snow drifts to get a good shot.” “The art keeps me warm,” Brumfield joked.

Despite his distinguished age—he will be 75 on June 28—Brumfield superbly orients himself with dates, remembers the tiniest details of his trips, remembers all the dates, when and where he did the shoots, names of all the churches. With a great sense of humor, he comments on his observations. “My first time in Ustituzhna we were with Vladimir Kudriavtsev, in the winter. At that time the head of the local administration was a communist, In general it was good working with communists.”

As for the question about whether he relates to photography as documentation or as a work of art, William noted that the one does not hinder the other. “Masterpieces in photographs—that is a bit mystical. Such a photograph should seize, should conquer from the first view. But patience is necessary. And fortitude. And a Uazik—without a Uazik you won’t get there.” The researcher remembered how in one of the churches on a hot July day, the light passed through the candle smoke and amazingly fell on the frescoes. “I stood here for a long time, and when a woman came up o me and asked what I was doing, I replied: ‘I am catching light’.”

Brumfield photogaphs not only Orthodox churches. “I photograph Buddhist lamaseries, mosques, Lutheran chuches, Catholic churches, synagogues. I am convinced that any House of God is deserving of respect. You have a multi-confessional country, a very rich culture—very complex and profound. And all of my books are nourished by this culture.”

Теги: William Brumfield